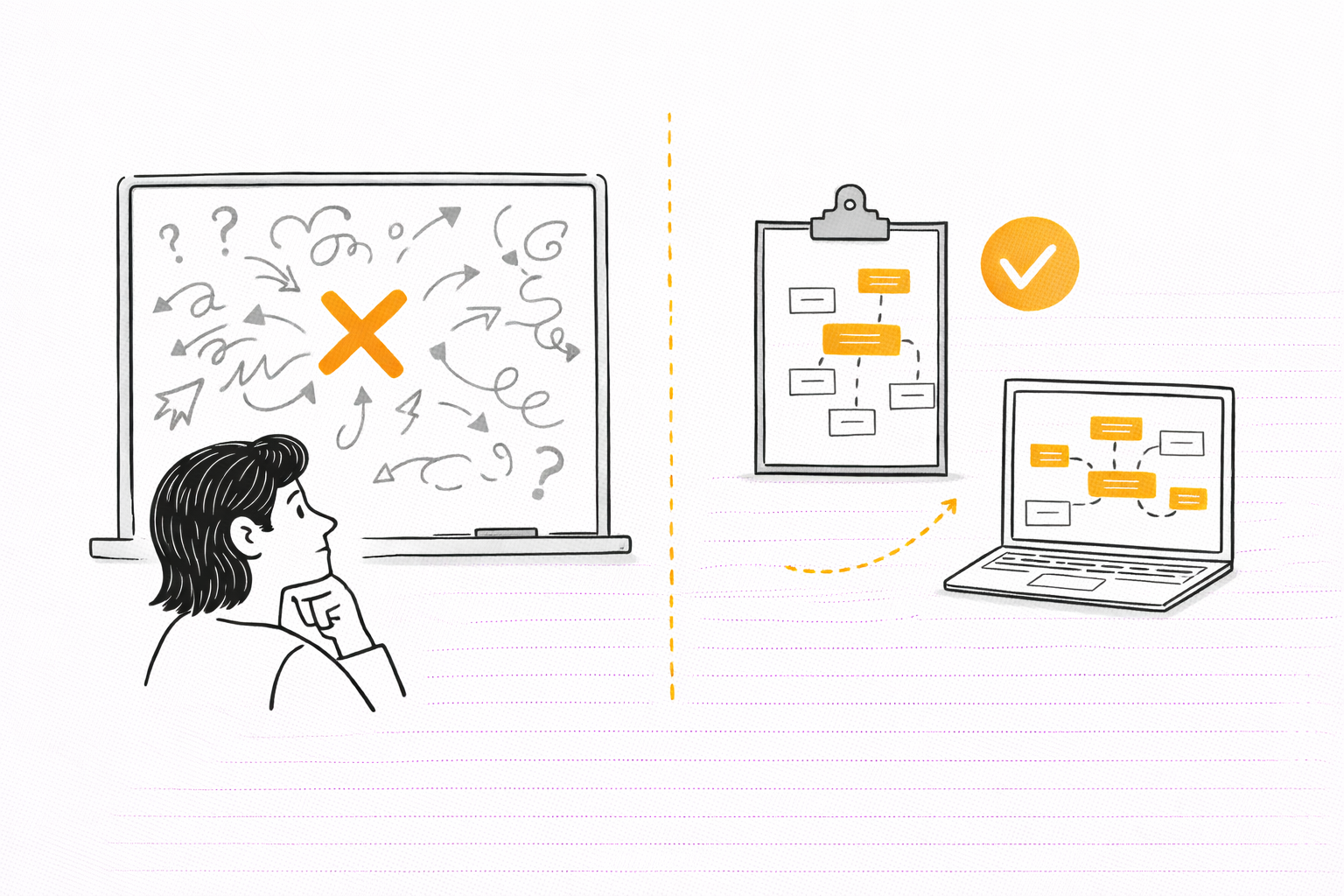

We reach for digital whiteboards when we need to think. They promise a clean slate, an infinite canvas where ideas can roam free, connect, and multiply. Yet, after the initial burst of sticky notes and sprawling arrows, we often find ourselves staring at a beautiful, colorful mess. The very tool designed to liberate thought can leave us feeling more lost than when we began.

The problem isn't a lack of ideas. It's that the space for thinking has become disconnected from the architecture of thought itself. We've mistaken the freedom to place anything anywhere for the freedom to think clearly. This is the paradox of the infinite canvas: it offers boundless room but provides no scaffold for meaning to crystallize.

The Infinite Canvas Paradox: Freedom That Constrains Thought

A physical whiteboard has inherent, productive constraints. Its edges force conciseness. The need to erase old ideas to make room for new ones demands prioritization. These limitations aren't bugs; they are cognitive features that guide us toward clarity.

Digital whiteboards remove these guardrails. The canvas scrolls forever. Nothing must be deleted. This should empower deeper exploration, but cognitive science suggests otherwise. Our visuospatial sketchpad—the part of working memory that handles visual and spatial information—has limited capacity. When ideas are scattered across a vast, unbounded plane, we expend significant mental energy just tracking their locations and relationships, leaving less capacity for the actual work of synthesis and insight.

The result is what we might call the "digital graveyard" effect. While specific studies on whiteboard abandonment are scarce, the pattern is familiar across digital tools. Projects are started with enthusiasm, become sprawling and unmanageable, and are eventually abandoned, left as monuments to unfinished thinking. The tool designed for "unstructured thinking" often prevents the emergence of any useful structure at all. Freedom of placement does not equal freedom of thought.

The most powerful thinking environments are not those with the fewest constraints, but those with the right constraints—ones that guide the mind toward coherence.

The Three Cognitive Gaps in Modern Whiteboard Tools

If infinite whiteboards are so problematic, why are they ubiquitous? They excel at one phase of thinking: collection. They are digital dumping grounds for sticky notes, images, and fragments of text. However, the journey from collection to understanding is where they reveal critical gaps.

Gap 1: The Synthesis Gap. Whiteboards are poor at synthesis. Connecting ideas is a purely manual, visual act—drawing a line between two sticky notes. This line carries no semantic weight; it doesn't specify if one idea supports, contradicts, or is an example of another. The tool doesn't help you reason through the relationship; it only helps you draw it.

Gap 2: The Hierarchy Gap. On a whiteboard, all elements are peers on a flat plane. While you can group items inside a frame, the tool has no native sense of parent-child relationships, dependency, or logical nesting. Hierarchy is implied by size or placement, not encoded in the structure itself. This makes it difficult to distinguish core principles from supporting details.

Gap 3: The Output Gap. The thinking captured often remains trapped on the canvas. Translating a sprawling whiteboard into a structured document, presentation, or plan requires a massive, manual translation effort. This friction breaks the flow from thought to communication, making the whiteboard a dead end rather than a conduit.

Imagine a whiteboard as a warehouse where you've dumped all the parts for a complex machine. You can see every gear and bolt, but building it requires you to manually find and connect each piece, with no blueprint. A structured thinking tool, in contrast, should provide both the parts bin and the intelligent scaffolding to assemble them into a coherent whole.

What Structured Thinking Actually Requires

Structured thinking is not about imposing rigid formalism. It is the process of making the relationships between ideas explicit, testable, and communicable. It requires an environment that supports three core modes:

- Divergence: The free generation of ideas (which whiteboards do well).

- Convergence: The synthesis of ideas into hierarchies, sequences, and logical models (which whiteboards do poorly).

- Expression: The fluid transformation of that structure into a shareable output.

This process needs intelligent constraints. A tree structure in a mind map, for example, is a constraint. It forces you to consider what is central and what is subordinate. This doesn't limit ideas; it gives them a scaffold on which to grow, reducing cognitive overhead by providing a reliable organizational principle. The visions of pioneers like Vannevar Bush's "Memex" were about creating "associative trails"—paths of reasoning—not infinite blank slates. The tool should have a gentle "opinion" about how knowledge coheres, guiding the user from initial chaos toward clarity.

Beyond the Whiteboard: Principles for Cognitive Tools

What would a tool designed for structured thinking look like? It would be built on principles that bridge the gaps left by the infinite canvas.

Principle 1: Semantic Over Spatial. Prioritize the logical relationship between ideas (e.g., "is evidence for," "is a step in") over their arbitrary X-Y coordinates. The structure carries meaning.

Principle 2: Dual-View Thinking. Support both a visual, non-linear view (for pattern recognition and creativity) and a linear, outline view (for logical sequencing and communication). The user should toggle seamlessly, as research into dual-view interfaces suggests they aid understanding by providing a global overview and detailed focus.

Principle 3: AI as a Structural Partner. Move beyond AI that merely generates content. Imagine AI that helps organize it—analyzing raw text to propose an initial hierarchy, suggesting connections you might have missed, or detecting gaps in logic based on semantic content, not just keywords.

Principle 4: Frictionless Input-to-Structure. The tool should accept raw, unstructured input—a URL, a PDF, a messy transcript—and propose an initial, editable structure. You start with a draft scaffold, not a paralyzing blank page. For instance, using a tool like ClipMind to instantly summarize a research paper into a mind map gives you a structured starting point for your own analysis, bypassing the blank-canvas dilemma entirely.

Principle 5: Living Output. The artifact you create should be directly usable as the skeleton for a report, a presentation, or a plan. The thinking medium and the output medium must be aligned, eliminating the painful "translation" step.

A Practical Shift: From Whiteboarding to Mind Mapping with AI

This brings us to a modern, rejuvenated practice: AI-augmented mind mapping. It is not the rigid, hand-drawn technique of the 1990s. It is a dynamic, interactive substrate for structured thinking that embodies the principles above.

Consider the workflow contrast:

- Whiteboard Workflow: Manually transcribe key points from a source onto sticky notes. Arrange and rearrange them visually. To create a document, you must manually rewrite everything from the canvas.

- Structured Thinking Workflow: Provide the tool with the source (a paper, a meeting transcript, a webpage). It generates an initial hierarchical map. You edit, rearrange, and question this structure. You brainstorm new branches in conversation with AI. Finally, you switch to outline view and your structured thoughts are already formatted for drafting.

The counter-argument is familiar: "But mind maps are too rigid!" A digital, editable mind map with AI collaboration is fundamentally different. The hierarchy is a starting hypothesis, not a final verdict. You are in a dialogue with a structure that can evolve. The AI acts as a partner, but the human remains the essential editor, critic, and final architect of thought.

Choosing Your Thinking Environment

The goal is not to declare whiteboards obsolete. It is to use them intentionally. The heuristic is simple:

- Use infinite whiteboards for early-stage, team-based ideation where the goal is quantity, free association, and collective gathering. They are excellent galleries of possibility.

- Use structured, AI-augmented tools for individual deep thinking, analysis, synthesis, and any task where the goal is a coherent understanding or a concrete output. They are workshops for building meaning.

Start by asking: "Is my primary goal to collect disparate ideas, or to build a structured understanding?" Match your tool to your cognitive phase. The future of thinking tools isn't one dominant platform, but a conscious stack: a capture tool, a structuring tool, and a communication tool, designed to work together with fluid handoffs.

The blank canvas will always call to us, symbolizing potential. But true breakthroughs happen when we move beyond the blankness and start building frameworks that can hold the weight of our ideas. Our tools should not just give us space to think; they should help us think in ways that leave a lasting, usable trace.