I open my browser. Twenty-seven tabs stare back. Each one a promise of insight, a fragment of a world I wanted to understand. A long-form essay on the history of cybernetics. A technical whitepaper. A YouTube lecture I swore I’d watch. Their tab titles are like tombstones, marking the spot where my attention died. My Kindle library is a graveyard of good intentions, filled with books boasting a proud “10% Read.”

This isn’t a personal failing. It’s the ambient condition of modern cognition. We have engineered the most powerful knowledge delivery system in history, yet we find ourselves stranded in a shallow stream of endless content, unable to drink deeply from any single source. In response, we’ve reached for a new class of tool: the AI summary. It promises a lifeline—the “gist” without the grind. But I’ve noticed a curious thing. The summaries, too, often go unread. They become just another item in the queue, another piece of content to skim.

The problem isn’t that we lack tools to finish things. The problem is that we’ve lost the cognitive posture required to finish anything at all. To understand why, we must look past the symptom—the unfinished article—and examine the architecture of our attention itself.

The Unfinished: A Modern Reading Condition

The data paints a stark picture of retreat. According to the National Endowment for the Arts, the share of U.S. adults reading any book for pleasure has slid from 54.6% a decade ago to 48.5%. For 13-year-olds, the decline is more precipitous: those reading for fun “almost every day” fell from 27% in 2012 to just 14% in 2023. This isn’t merely a shift from print to pixel; it’s a fundamental change in engagement. Online, our commitment is even more fleeting. Research indicates the average attention paid to a single screen is now about 47 seconds, down from 2.5 minutes just two decades ago. Scroll depth—how far down a page we go—dropped 7% in 2025 alone.

We are in a state of perpetual cognitive reconnaissance, surveying landscapes of text but seldom inhabiting them. The tension is palpable: we have more access to knowledge than ever, yet we feel a growing poverty of understanding. The AI summary arrives as a proposed cure for this anxiety. It offers the illusion of closure, the satisfaction of a checkbox ticked. But this is a false promise. It treats the symptom—length—while ignoring the disease: an attention system trained for fragmentation.

The real inquiry begins not with asking how we can finish more, but why we’ve lost the capacity for deep finish in the first place.

The Architecture of Interruption: How Our Tools Train Us to Skim

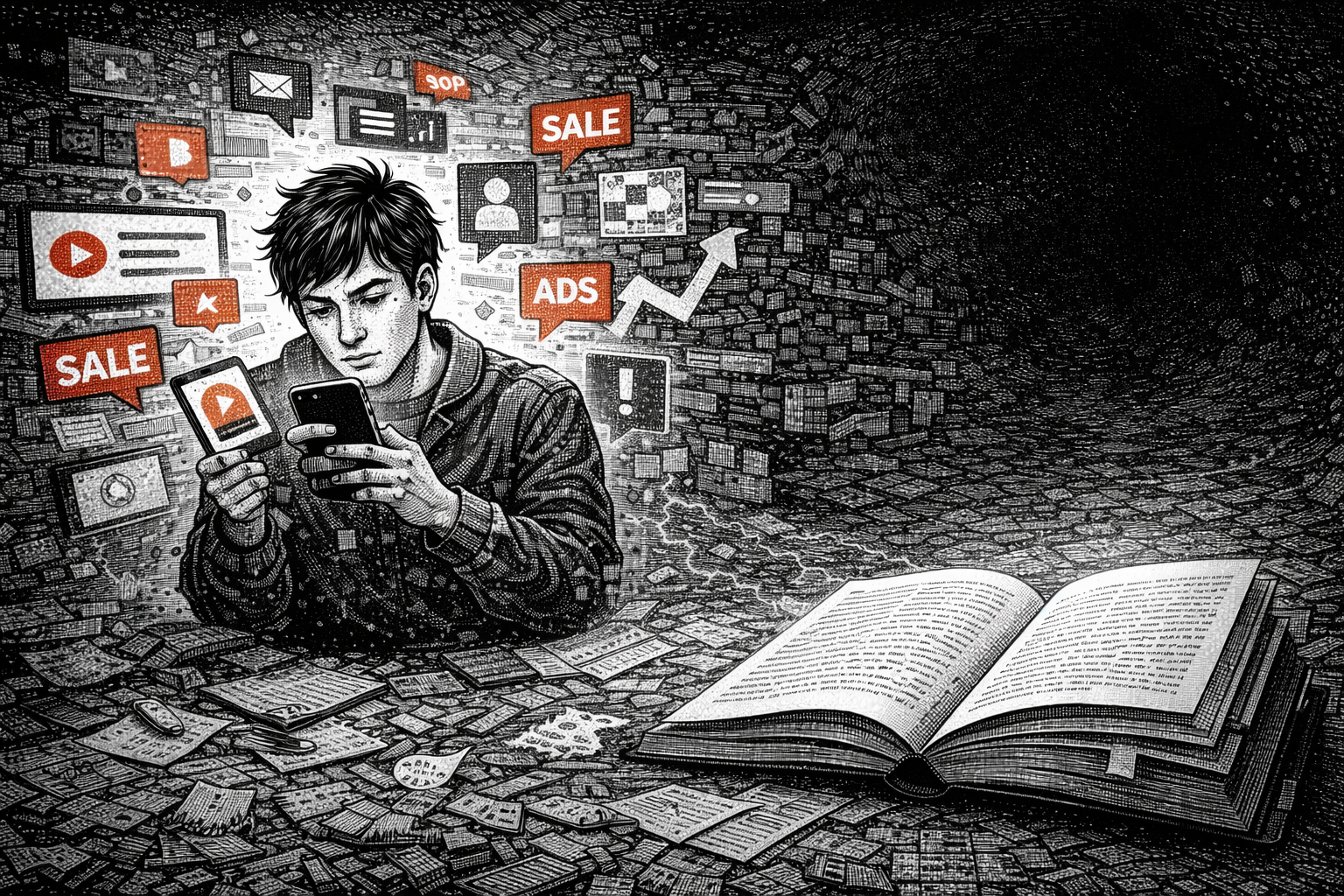

Our digital environments are not neutral spaces. They are conditioning systems, meticulously designed to shape behavior. The infinite scroll, the algorithmic feed, the push notification—these are not features; they are behavioral engines. They operate on a principle of variable rewards, a slot-machine logic where the next piece of content might be the one that delivers the dopamine hit. This conditions us to seek novelty over depth, to value the thrill of the new over the satisfaction of the complete.

Contrast this with the physicality of a printed book. Its interface is its binding. It has a clear beginning, middle, and end. It demands linear progression and physical commitment. You feel its weight diminish in your left hand and grow in your right. Our current interfaces demand the opposite: fragmentation, non-linearity, and a readiness to abort. The consequence is that we develop what I call “interruption-ready” cognition. Our mental state becomes one of vigilant preparedness, always waiting for the next ping, the next highlight, the reason to switch.

This comes at a profound cognitive cost. Psychologists studying task-switching have found that shifting between even simple tasks can cost up to 40% of a person’s productive time. Notifications, the primary delivery mechanism for interruptions, have been shown to be detrimental to performance and increase strain. We are not just skimming text; we are living in a cognitive environment that makes deep reading, an activity requiring sustained, unbroken focus, feel alien and effortful. The medium has trained us out of the skill.

We are not just skimming text; we are living in a cognitive environment that makes deep reading feel alien and effortful.

The AI Summary Paradox: Efficiency Without Understanding

Enter the AI summary, the logical endpoint of this optimization for speed. Its value proposition is seductive: extract the essence, discard the filler, give me the coordinates so I don’t have to walk the map. But this confuses information with understanding.

Comprehension is not a process of data extraction. It is often a journey built on the author’s scaffolding—the careful buildup of an argument, the illustrative example, the narrative turn that reshapes your perspective. A summary gives you the conclusion but severs it from the reasoning that makes it credible and meaningful. It is consumptive, not constructive. You receive a finished product, bypassing the critical, effortful work of building your own mental model of the content.

This bypass has consequences. In cognitive science, the concept of “desirable difficulties” posits that certain hurdles during learning—like generation, spacing, and variation—enhance long-term retention and understanding. The struggle to follow a complex argument, to connect ideas, to restate a point in your own words, is not a bug in the learning process; it is the feature. When we outsource that struggle to an AI, we risk what I call “summary dependency”—a familiarity with conclusions without the ability to reconstruct the logic that supports them.

The paradox deepens: we turn to summaries to cope with information overload, but in doing so, we may be eroding the very cognitive muscles we need to engage with complex texts when it truly matters. We use a tool for efficiency that, over time, can make us less capable of the depth we sought in the first place.

From Passive Consumption to Active Structuring

If the goal is not merely to “finish” more content, what should it be? I propose a shift in objective: from completion rate to integration rate. The metric of success changes from how many things you’ve consumed to how deeply you’ve woven a few critical ideas into your own thinking.

This requires moving from passive consumption to active structuring. “Active reading” in the digital age must go beyond highlighting text. It must involve the immediate, real-time transformation of consumed information into a personal, editable structure. When you encounter a compelling article, the goal should not be to simply reach the end, but to externalize its architecture as you read.

The cognitive benefit is twofold. First, the act of mapping forces you to identify relationships, hierarchies, and core arguments. You cannot passively absorb; you must actively decide what connects to what. Second, this process creates a “cognitive scratchpad” outside your mind. As researcher David Kirsh has argued, external representations change the cost structure of thinking, allowing us to offload working memory and engage in more complex reasoning.

This turns reading from a linear, consumptive pass into a non-linear, constructive dialogue. You are no longer just a passenger following the author’s path. You are a cartographer, building a parallel model of the territory in your own mind—and on your screen.

Tools for Thought, Not Just for Summary

Most of our current tools are ill-suited for this active structuring. Read-it-later apps are digital hoarding cabinets, places where content goes to be forgotten. Blank document editors offer freedom but no scaffold, demanding creation ex nihilo. We lack tools designed for the vital, messy middle phase: synthesis.

A tool for active structuring needs a few core principles:

- Frictionless Capture: It must start from anywhere—a browser tab, a PDF, a video link—with minimal effort.

- Visual Malleability: The structure must be as editable as thought itself, allowing you to rearrange, connect, and annotate as understanding evolves.

- Integrative Power: It should allow new ideas to connect to old ones, building a personal knowledge base over time.

Imagine this workflow: You open a long, complex article. With one click, you generate an initial structural map—a scaffold of main headings and key points. This is where an AI can genuinely assist, not by giving you the answers, but by providing a starting canvas. Then, you read actively. As you go, you drag nodes, merge sections the AI got wrong, add your own annotations and connections in the margins. The map is no longer a summary of the article; it is a living document of your engagement with it. Finally, you isolate the most powerful insights and drag them into your permanent knowledge base, connecting them to related ideas from past readings.

The outcome is not a saved URL or a bullet-point list. It is a personalized knowledge artifact—a tangible, visual representation of your understanding. This artifact is what you “finish” building. The act of reading becomes a means to this end.

I built ClipMind from this frustration. I wanted a space where I could start with the AI-generated scaffold of a webpage or a research paper, but then immediately begin bending it, breaking it, and rebuilding it into a map that reflected my own questions. The tool’s value isn’t in the summary it produces, but in the structured thinking it facilitates as you edit. You can switch between the mind map and a linear Markdown view, toggling between visual exploration and written synthesis. The goal is to close the gap between encountering an idea and making it your own.

Reclaiming Depth in an Age of Fragments

The crisis of the unfinished is, at its heart, a crisis of misplaced optimization. We have optimized our systems for intake velocity and novelty at the direct expense of comprehension density and depth. The solution is not to read faster or to lean harder on summaries to do our thinking for us. It is to fundamentally change the nature of the interaction from one of consumption to one of co-creation.

This is a deliberate, subversive practice. It means choosing depth over breadth in the moments that matter. It means using technology not as a bypass for engagement, but as a lever to deepen it. It means recognizing that the struggle to understand is not an inefficiency to be eliminated, but the core of the learning process itself.

Perhaps we don’t need to finish everything. Our tab graveyards can be peaceful resting places for curiosities that didn’t warrant a full excavation. But for the ideas that are worthy—the ones that challenge us, that resonate, that could change our thinking—we need more than a summary. We need tools and habits that allow us to truly finish thinking about them. We need to build maps, not just collect coordinates.