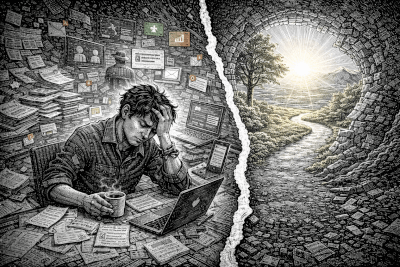

We have more tools, more data, and more connectivity than any generation of thinkers before us. Yet, a quiet, persistent anxiety hums beneath the surface of modern knowledge work: the feeling of being perpetually busy but never truly clear.

You know the sensation. It’s the end of a day spent answering emails, hopping between browser tabs, and attending back-to-back meetings. The activity log is full, but the sense of accomplishment is hollow. You’ve processed information, but you haven’t understood it. You’ve been reactive, but not creative. This is the core paradox of our time: information abundance paired with clarity scarcity.

This isn’t a personal failing; it’s a systems design problem. The very interfaces that promise productivity—linear documents, infinite-scroll feeds, and notification-driven apps—are architected for consumption and communication, not for comprehension and synthesis. They keep us busy managing the flow, but they leave us stranded when we try to see the shape of the river.

The Architecture of Busyness: How Our Tools Fragment Thought

Our standard toolkit enforces a sequential, atomized model of thinking. You write one email. You read one paragraph. You respond to one chat message. Each action is a discrete brick in a wall you cannot see. The interface presents a flatland of tabs and windows, where every task demands an equal, immediate slice of your attention.

This design has a profound cognitive cost. Research shows that task-switching might cost up to 40% of a person's productive time, and knowledge workers toggle between applications over 1,200 times per day, losing hours each week to micro-recoveries. This is more than lost time; it’s cognitive load spillover. When the mental model of a complex task—understanding a research paper, planning a product launch—doesn’t fit the tool’s linear, fragmented structure, the excess mental burden falls entirely on you. You are left trying to hold the architecture of a cathedral in your head while your tools only hand you bricks, one at a time.

Contrast this with tools designed for architectural thinking. A mind map, a system diagram, or a concept canvas makes relationships and hierarchy explicit from the start. It externalizes the structure, freeing your working memory to analyze, connect, and create, rather than just remember.

The feeling of ‘busy’ is the friction of your mind working against a tool’s limitations. The feeling of ‘clear’ is the resonance of your mind working with a tool’s affordances.

Clarity as a Visual, Relational Construct

We often mistake clarity for a linear endpoint: “I’ll be clear once I finish reading this report.” But true clarity is not a destination reached by accumulating more facts; it is a relational state achieved by seeing the connections between facts.

Our brains do not natively think in bullet points or paragraphs. They think in networks, associations, and spatial relationships. A list of ten project risks is data; a map showing how those risks influence one another is insight. The map reveals the hierarchy (which risk is foundational?), the connections (does risk A amplify risk B?), and the gaps (what have we missed entirely?).

This aligns with the philosophy of thinkers like Bret Victor, who argued that creators need an immediate connection to what they’re creating. For the knowledge worker, this means needing an immediate connection to the structure of their knowledge. The moment of clarity is that “aha” when an internal, fuzzy mental model finds a coherent, external representation. It’s the shift from holding ideas in tension to seeing them in relation.

The Missing Layer: From Information Capture to Knowledge Structure

Our workflows have a gaping hole. We have excellent tools for the beginning and the end: for capturing information (read-it-later apps, note-taking) and for presenting it (decks, polished documents). But the critical middle layer—where captured fragments are compared, contrasted, merged, and synthesized into new understanding—is a desert.

This missing structuring layer is where the real work of thinking happens. Without it, we default to the path of least resistance: we accumulate more captures (busy) instead of refining the structures they imply (clear). Our notes apps become digital graveyards of good intentions.

This is where a new class of tools, and a new role for AI, emerges. The promise is not AI as a content generator, but AI as a structuring co-pilot. Imagine a tool that can take a dense article, a meandering meeting transcript, or a complex research PDF and propose an initial, editable visual structure—a first draft of understanding. This is the vision behind tools like ClipMind, which act as that missing layer, turning unstructured inputs into structured, visual maps you can immediately work with and refine. The AI handles the initial heavy lifting of pattern recognition, but you retain agency over the final architecture. It’s a partnership aimed at accelerating the journey from information to insight.

Building a Practice of Clarity: Principles Over Hacks

Moving from busy to clear requires a shift in practice, not just another life-hack. It’s about adopting principles that favor synthesis over accumulation.

- Make the Structure Visible Early: Don’t wait until the end of your research to outline. Start with a visual map, however rough. The act of creating it will reveal what you know and, more importantly, what you don’t.

- Separate Gathering from Structuring: Designate distinct modes. Use one tool or time block for voracious capturing (reading, highlighting). Then, switch to a different interface—a canvas, a diagramming tool—dedicated solely to organizing and connecting those captures.

- Use Tools That Allow Emergent Reorganization: Knowledge is not static, and its representation shouldn’t be either. Favor tools where you can drag, drop, merge, and re-parent ideas effortlessly. Your thinking will evolve, and your tools should evolve with it.

- Seek Compression, Not Collection: The goal is to distill many inputs into a simpler, more powerful model. Ten interconnected nodes on a map that you understand deeply are infinitely more valuable than one hundred orphaned notes in a list.

- Embrace the Edit: Clarity is iterative. Your first visual structure is a hypothesis. Refining it—collapsing redundant branches, drawing new connections, questioning hierarchies—is the core work of thinking.

The Toolmaker's Responsibility: Designing for Coherence

For those of us who build tools, the clarity deficit is a design challenge we must own. We have inherited interfaces optimized for transaction and now must design ones optimized for thought.

This means prioritizing the user’s cognitive model over the software’s data model. The interface should reveal relationships, not hide them in database tables. It means building “low-floor, high-ceiling” systems—tools as simple as pasting a URL to get a structured summary, but powerful enough to let a researcher merge a dozen maps into a unified framework for a literature review.

AI’s role here is as an accelerator for the structuring layer, reducing the friction of starting, not removing the agency of thinking. The measure of a tool’s success should shift from “time saved” to “clarity gained.” Does using this system leave the user with a better, more coherent understanding than they started with?

From Busy to Clear: A Personal Reckoning

The shift begins with a simple, personal audit. At the end of your next work block, ask: “Do I feel busy, or do I feel clear?” Your answer is a direct diagnosis of your tool fit.

Try a small experiment. Take one complex task—understanding a competitor’s strategy, planning a blog post, synthesizing feedback—and force yourself to start in a visual structuring tool. Dump your notes, quotes, and ideas onto a canvas and spend time only moving them around, drawing lines, and grouping concepts. Resist the urge to write prose. Notice the difference in your mental state. The anxiety of the blank page often gives way to the curiosity of an emerging pattern.

Systemic change in how we work is slow, but the choice of your personal tools is immediate. You can choose interfaces that favor coherence, even if your organization’s default stack does not. In an age defined by infinite information, the scarcest resource is no longer access to knowledge, but the sustained clarity to use it well. Our tools, and our habits, must be rebuilt to cultivate that clarity.