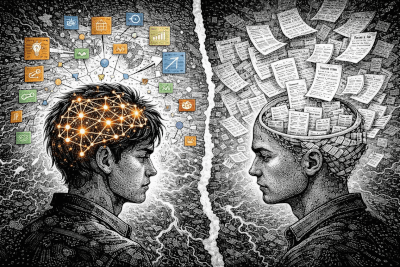

We often talk about thinking styles as if they were preferences—some people are “visual,” others “verbal.” But what if this distinction runs deeper than taste? What if linear text thinking and spatial visual thinking represent fundamentally different cognitive architectures, each with its own strengths, constraints, and internal logic?

The tension is not merely about how we prefer to receive information, but about how we structure reality in our minds. On one side lies the sequential, propositional world of text, built on hierarchy and narrative. On the other, the relational, systemic world of visuals, built on pattern and space. For centuries, our primary tools for thought—the book, the essay, the report—have privileged the former, often forcing complex, interconnected ideas into a single, linear path.

This isn’t about learning styles; it’s about cognitive ergonomics. Are we using the right mental architecture for the problem at hand? And more importantly, are our tools forcing one mode onto tasks better suited for the other, creating unnecessary friction in how we understand, create, and communicate?

The Unseen Architecture of Thought

Consider the act of reading this paragraph. Your mind is likely following a chain: one word, one clause, one sentence after another. This is the architecture of text thinking—sequential, hierarchical, and deeply linguistic. It excels at building arguments, telling stories, and moving from premise to conclusion. Its roots are in the logical structures of language itself.

Now, picture a mind map of this article’s key ideas. Your eyes dart from a central node to various branches, seeing relationships and hierarchies simultaneously. This is the architecture of visual thinking—spatial, relational, and systemic. It excels at showing the whole, revealing patterns, and managing complexity. Its roots are in our brain’s innate capacity for spatial navigation and pattern recognition.

Historical thinkers have long embodied this divide. Vannevar Bush’s vision for the Memex was not a linear document but a device for forging “associative trails”—a fundamentally visual, networked model of knowledge. He imagined leaping from idea to idea as one might traverse a landscape, a stark contrast to the traditional, linear procession of a written treatise.

The question is not which is better, but what each architecture optimizes for. Text thinking gives us the logic of sequence. Visual thinking gives us the logic of space. When we mistake one for the other, or force a translation too early, we pay a cognitive tax.

Text Thinking: The Logic of Sequence

Text thinking is our default mode for rigorous communication. It is a cognitive process built on sequence, subordination, and propositional logic. Its great strength is its ability to enforce a single path of reasoning, which is why it remains the bedrock of law, philosophy, and formal argument.

Its power comes from constraints. By forcing ideas into a linear stream, text thinking excels at:

- Causal Reasoning: Establishing clear “if-then” relationships.

- Narrative Construction: Building meaning through time, with a beginning, middle, and end.

- Precision: Demanding exact definitions and eliminating ambiguity through careful phrasing.

However, these constraints are also its limitations. Text thinking struggles with simultaneity. It cannot easily represent multiple, equally valid relationships existing at once. Describing a complex system—like the interactions within an ecosystem or a software architecture—in pure text often results in a fragmented, chapter-by-chapter account that loses the sense of the whole.

This is the “scrolling” problem. Our digital interfaces for text—the word processor, the PDF reader—mirror and reinforce this sequential cognition. You can only see one page, one paragraph at a time. To understand the structure, you must hold it in your working memory or constantly jump back and forth, a process that increases cognitive load.

Text thinking is like building a chain, link by meticulous link. The direction is strong and clear, but you can only follow one path at a time.

Visual Thinking: The Logic of Space

Visual thinking operates on a different plane. It is a cognitive process built on proximity, connection, and spatial arrangement. Its strength is synthetic and intuitive, allowing us to grasp complex wholes and see relationships that linear logic might miss.

This mode leverages our brain’s powerful visual-spatial sketchpad. By externalizing ideas into a spatial layout, we effectively expand our working memory. We can manipulate relationships directly, moving nodes, grouping clusters, and testing new configurations without losing sight of the overall structure.

Its advantages are profound for certain tasks:

- Pattern Recognition: Seeing trends, gaps, or clusters that are invisible in a list.

- Managing Complexity: Holding many interrelated parts in view simultaneously.

- Abductive Leaps: Making intuitive connections between distant ideas, fostering creativity and discovery.

History is filled with breakthroughs born from this visual shift. John Snow’s 1854 dot map of cholera cases visually linked the disease to a single water pump, overthrowing the prevailing “miasma” theory and founding modern epidemiology. The visual representation made the pattern undeniable in a way a textual report could not.

Yet, visual thinking has its own constraints. It can lack the precise, step-by-step rigor needed for formal proof or detailed instruction. A beautiful diagram may show “what” and “how things relate,” but often struggles to articulate the precise “why” in a defensible, linear argument.

Visual thinking is like arranging landmarks on a map. You see all the connections and terrain at once, but the specific route of explanation—the narrative—must be chosen and articulated afterward.

The Cognitive Cost of Translation

The deepest friction in our thinking workflows isn’t within one mode, but in the transition between them. We often think in a spatial, relational way—juggling concepts, seeing overlaps—but are forced to communicate in linear text. The mental effort of translating a rich, multidimensional understanding into a single-threaded document is immense and lossy.

This is the translation loss. Nuances of relationship, alternative groupings, and the sheer shape of the idea can get flattened in the process. Conversely, trying to build a coherent diagram from a dense, linear report requires reverse-engineering the author’s implicit mental model, which may not match the document’s explicit structure.

The problem is exacerbated by our tools. Most are monogamous. Word processors are for text. Diagramming tools are for visuals. This forces a premature commitment to an architecture. Do you start outlining in a doc, potentially locking ideas into a hierarchy too soon? Or do you start diagramming, risking a structure that’s difficult to narrativize later?

This premature crystallization is a major blocker to fluid thought. It’s why the most agile thinkers often retreat to low-fidelity, hybrid tools like whiteboards or napkins—surfaces that impose no formal structure and allow effortless shifting between doodles, keywords, and arrows.

Beyond the False Dichotomy: Tools for Cognitive Bilingualism

The goal is not to crown a winner, but to achieve fluency in both architectures and the ability to translate between them with minimal friction. We need to cultivate cognitive bilingualism.

A cognitively bilingual thinker knows when to deploy a spatial map to explore a problem space and when to switch to a linear outline to test an argument’s logic. The key is having tools that support this non-destructive movement between representations. A change in the visual map should reflect in the linear outline, and vice versa. The two views are not separate files, but different lenses on the same underlying model of thought.

This is where the integration of AI can shift from being a content generator to a cognitive partner. Its role is not to think for you, but to reduce the translation overhead. It can suggest a visual structure from a block of text, revealing hidden hierarchies. Conversely, it can help generate a narrative flow from a cluster of nodes on a map. For instance, using a tool like ClipMind to summarize a research paper instantly gives you a spatial overview, allowing you to see the argument’s skeleton before you write a single note. The AI handles the initial, heavy-lift translation from linear text to spatial structure, freeing you to think with the ideas, not just about their sequence.

The principle is bidirectional linking. The visual and the verbal should be in dialogue, each informing and refining the other.

Crafting a Hybrid Thought Process

So what does a practical, hybrid thinking workflow look like? It’s less about a rigid sequence and more about intentionally applying the right architecture for each phase of thought.

Phase 1: Discovery & Synthesis (Visual Dominant) This is the gathering and connecting phase. Whether you’re researching a topic, analyzing user feedback, or brainstorming ideas, start spatially. Dump information into a canvas. Use a tool to summarize webpages or PDFs into mind maps to quickly see core themes and relationships. The goal is to avoid linearizing too early. Let unexpected connections emerge from proximity and grouping.

Phase 2: Structuring & Logic (Hybrid) Once the landscape is visible, impose narrative order. This is where you switch lenses. Take your visual map and switch to an outline or linear view. Does the logical flow of an argument emerge from the spatial relationships? Drag nodes in your map to see how it changes the outline. This phase is for testing the coherence of the story you want to tell, using both spatial intuition and linear logic.

Phase 3: Communication & Refinement (Text Dominant) Now, with a structurally sound outline derived from your map, move into your word processor or note-taking app. Draft with precision. Here, the visual map acts as your “source of truth” diagram. Periodically refer back to it to ensure your linear text hasn’t inadvertently dropped a crucial connection or sub-topic. The writing process will inevitably generate new insights—feed these back into your visual model.

This process is a loop, not a line. Thinking is recursive, and our tools should allow us to cycle through these phases with minimal resistance.

The Future of Thinking Tools

We are on the cusp of moving beyond static documents and isolated diagrams. The future of thinking tools lies in dynamic, bi-modal canvases where text and visuals are first-class, bidirectionally linked citizens.

The ideal tool supports the full cognitive cycle: it ingests heterogeneous information (text, video, data), helps you auto-structure it visually, allows you to manipulate that structure with direct manipulation, and then lets you export or pivot into a coherent linear format—all within a single, continuous environment. The measure of success will not be features, but reduced cognitive overhead. Does the tool dissolve the friction between having an idea and structuring it? Between understanding a complex source and expressing your synthesis?

The great divide between visual and textual thinking isn’t fundamentally in our minds; we are capable of both. The divide has been in our tools, which have historically forced a choice. By building tools that honor both cognitive architectures and facilitate translation between them, we can begin to think in ways that were previously constrained by the medium itself. We can build chains when we need direction, and maps when we need to see the territory—and, most importantly, know how to turn one into the other without losing the soul of the idea.