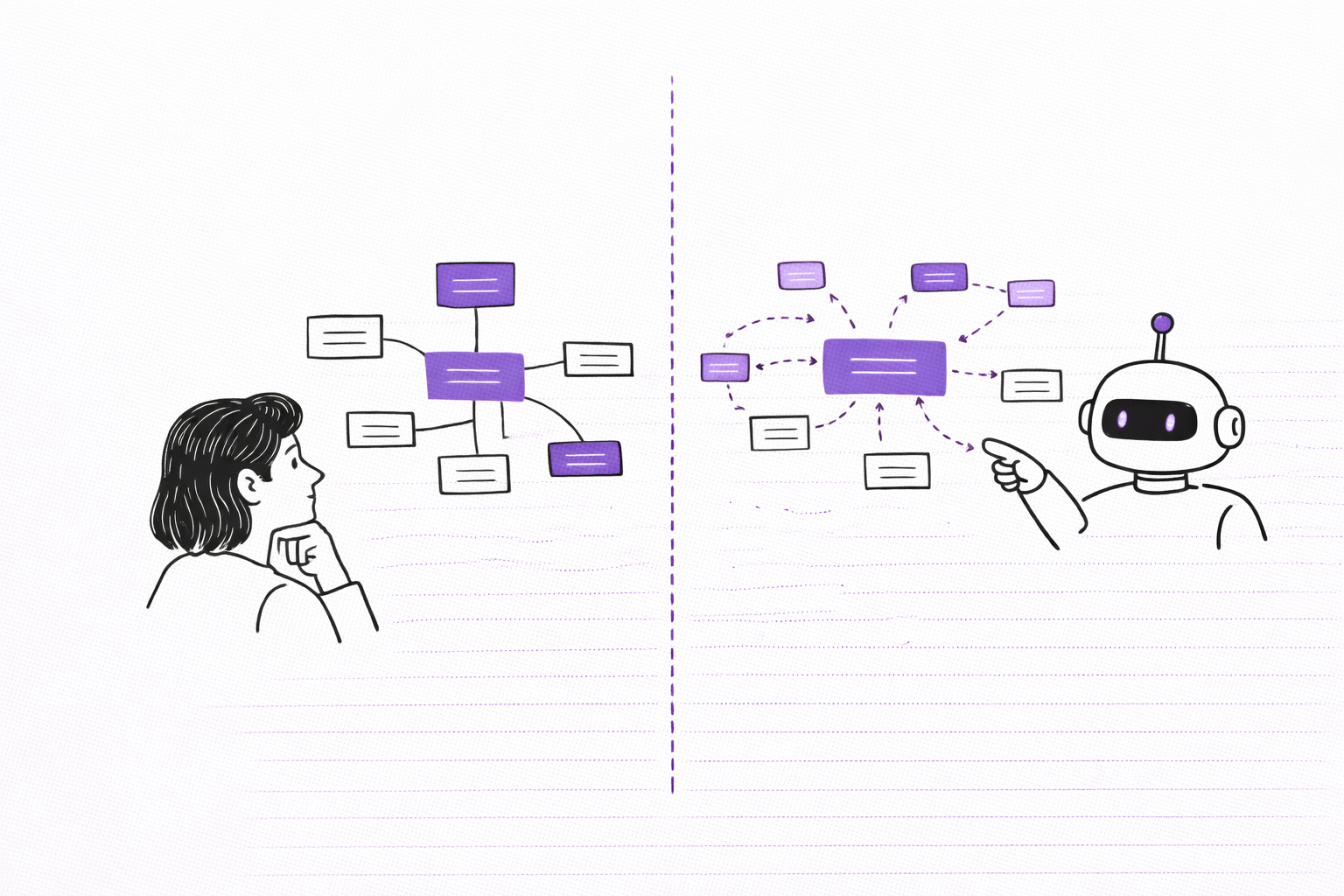

We stand at a curious crossroads in the history of thinking tools. For decades, the mind map has been a symbol of personal cognition—a radial explosion of ideas, drawn by hand, that externalizes the unique contours of one’s own mind. Today, with a click, an algorithm can generate a similar-looking structure from a YouTube lecture, a research paper, or a sprawling AI chat. The visual output may resemble the old form, but the cognitive journey to create it is fundamentally different. This isn’t merely a shift in efficiency; it’s a transformation in how we relate to our own thoughts and the information we consume. The real difference between a traditional mind map and an AI-generated one isn’t found in the branches and nodes, but in the underlying tension between structure we impose and structure we discover.

The Cognitive Tension: Structure Imposed vs Structure Discovered

When you draw a mind map by hand, you are engaged in an act of construction. You start with a central idea—perhaps “Project Launch”—and your branches emerge from what you already know, what you consciously consider important. The connections follow your associative thinking: “Marketing” links to “Budget” because in your mental model, they are related. The map is a snapshot of your existing understanding, a portrait of your cognitive landscape drawn from memory.

An AI-generated map operates on a different principle: pattern recognition. Given a source—a 45-minute product management webinar, for instance—the algorithm analyzes the text, identifies statistical relationships between concepts, and infers a hierarchy. It doesn’t “know” anything; it surfaces patterns. The resulting map might connect “User Feedback” to “Q4 Roadmap” not because the creator initially saw the link, but because the source material discussed them in proximity with significant semantic weight.

This is the core tension. A manual map reflects confirmation bias; it organizes the world to fit the mapmaker’s pre-existing narrative. An AI map reflects the bias of its training data and the source material; it presents a narrative discovered in the text, which may challenge or expand the reader’s perspective. Research on learning underscores this distinction, showing that self-generated knowledge structures engage different cognitive pathways than externally provided ones. The former strengthens personal schema, while the latter can introduce novel frameworks.

The hand-drawn map asks, “What do I think?” The AI-generated map asks, “What does this text think?”

This duality presents not a right or wrong answer, but two complementary modes of cognition. One is introspective and synthetic; the other is analytical and revelatory.

Architectural Differences: Hierarchical vs Networked Thinking

Look closely at the structures, and the philosophical divergence becomes visual. The classic, manual mind map is a radial hierarchy. A central node, thick branches, thinning sub-branches—it’s a tree. This form is cognitively comfortable; it mirrors the limitations of human working memory, which favors clear parent-child relationships and linear progression. It’s designed for clarity and memorability, often at the expense of complexity.

AI-generated maps, unburdened by the need to be drawn in real-time by a human, frequently reveal a more networked architecture. While they often have a hierarchical backbone, they are more likely to include lateral connections, cross-links, and clusters that a human building linearly might overlook. The algorithm can identify that a concept mentioned early on is deeply related to one mentioned much later, drawing a connecting line across the hierarchy.

This structural difference has practical implications. The tree is easier to navigate and is excellent for presenting a finalized plan or studying for a test. The network can handle higher information density and is better for analysis, revealing the true, often messy, interrelatedness of a complex topic. Studies on information visualization suggest there is no single “best” structure; optimal information architecture depends on the cognitive task—learning, analysis, or creative ideation.

In Practice: A product manager mapping a vision from their own head will likely produce a clean, goal-oriented hierarchy. That same manager using an AI tool to summarize ten competitor analysis documents might receive a map dense with cross-functional themes—like “pricing strategy” linked to “customer support channels”—revealing industry patterns they hadn’t manually connected.

The Creation Process: Deliberate Craft vs Instant Synthesis

The experience of time separates these tools profoundly. Crafting a mind map by hand is a slow, deliberate thinking process. The value isn’t just in the final artifact; it’s in the act of creation. The thinking happens as you decide where to place each node, as you pause to consider a connection. It’s a form of cognitive wrestling, where the friction of manual creation generates heat and light in your understanding.

AI mapping is an act of instant synthesis. You provide the raw material—a webpage, a PDF—and in seconds, a structure is externalized. The “thinking” has already been done (by the author of the source material), and the AI performs a rapid autopsy, organizing the findings. This enables a different kind of analysis: rapid scanning, pattern discovery across vast information sets, and the freeing of cognitive resources from organization to interpretation.

Neurological evidence hints at the deep benefits of the manual process. The act of drawing or manually creating visual structures co-activates multiple sensory and motor regions of the brain, creating a richer, more durable memory trace. The speed of AI generation, while powerful for overview, may bypass some of this encoding depth. The question becomes one of cognitive economy: when do you need the deep, durable understanding that comes from construction, and when do you need the rapid, broad insight that comes from computational synthesis?

Bias and Perspective: The Mapmaker’s Hand vs The Algorithm’s Lens

Every map is a reduction of territory, and every reduction involves a perspective. A manual mind map makes its bias transparent. What’s included, emphasized, or omitted is a direct reflection of the creator’s priorities, knowledge gaps, and blind spots. The bias is visible in the empty spaces and the thick, confident lines. Editing this map means refining your own thinking.

An AI-generated map carries a different kind of bias. It reflects the biases in its training data, the design of its algorithms, and the selection and quality of the source material. If the source article has a strong slant, the map will codify that slant into its structure. If the AI model has been tuned to prioritize certain semantic relationships, that tuning shapes the output. These biases are often opaque, buried in layers of code and data. Editing this map often means adjusting prompts, tweaking parameters, or regenerating.

This leads to a critical difference in perceived authority. Studies on credibility show users often perceive AI-generated content differently than human-created content, wrestling with questions of trust and authenticity. A self-drawn map is inherently authentic but limited to one’s own mind. An AI-drawn map feels authoritative but its provenance is murky. The most responsible approach is to treat the AI-generated map not as a final authority, but as a provocative interlocutor—a lens that offers a specific, algorithmically-derived view of the territory, always worth questioning.

Practical Applications: When to Use Which Approach

The goal is not to choose a side, but to develop metacognitive awareness—the ability to select the right tool for the thinking task at hand.

Use manual mapping when:

- Learning a new concept from scratch: The struggle to build the structure yourself is where learning occurs.

- Brainstorming creatively: Generating original ideas requires the free, associative wandering of your own mind.

- Personal reflection and planning: Aligning a project or goal with your internal values and mental models.

Use AI-generated mapping when:

- Analyzing large, complex documents: Quickly extracting the core architecture from a research paper, legal document, or lengthy report.

- Discovering hidden patterns: Using a tool like ClipMind to summarize multiple competitor webpages or a series of user interview transcripts, revealing cross-cutting themes you might have missed.

- Creating a first draft structure: Generating a starting point for an essay, article, or presentation outline from a collection of notes or sources.

The most powerful workflow is often a hybrid. This is where next-generation tools show their promise. Start with an AI to synthesize: feed a long article into a summarizer to get an initial, structured overview. Then, switch to manual mode. Drag the AI’s nodes into an order that makes sense to you. Add your own insights as new branches. Delete connections that feel wrong and draw new ones that reflect your synthesis. You begin with discovered structure and end with an imposed structure that has been reconciled with your own understanding. Case studies of effective hybrid approaches highlight this as a best practice across professions, from students conducting literature reviews to product managers synthesizing market research.

The Future of Visual Thinking: Augmentation, Not Replacement

The evolution here points away from replacement and toward augmentation. The real difference between traditional and AI-assisted mapping will blur as tools evolve from being mere generators to becoming collaborative thinking partners. Imagine a system that learns from your manual edits—when you consistently disconnect two AI-proposed nodes or create a new cluster—and uses that feedback to improve its future suggestions for you personally.

The philosophical shift is profound. We are moving from tools that help us express what we already think, to tools that help us discover thoughts we didn’t know we had. This aligns with emerging research on human-AI collaborative thinking, which frames AI not as an oracle but as a catalyst for augmented cognition. The design challenge for the next generation of knowledge tools is cognitive ergonomics: creating seamless, intuitive transitions between manual and AI-assisted modes, where the human remains the architect of meaning and the AI serves as an incredibly well-read, pattern-recognizing assistant.

Embracing Cognitive Diversity

The dichotomy between the hand-drawn branch and the algorithmically-generated node is, ultimately, a false one. Both are expressions of the same human desire: to understand, to organize, and to see connections. One method draws the map from the inside out, the other from the outside in. The most effective thinkers and learners won’t pledge allegiance to one method but will develop fluency in both.

They will know when to slow down and craft, building understanding through the friction of creation. They will know when to leverage synthetic power, using AI to illuminate patterns and manage scale. The real skill of the future is not just thinking, but orchestrating thinking—knowing which cognitive tools to employ, and how to weave their outputs into a coherent, personal understanding. In the end, these tools are mirrors. Traditional mind maps show us the current shape of our minds. AI-generated maps show us the shapes hidden in the world’s information. The wisest course is to look into both mirrors, and navigate the territory with both maps in hand.