We live in an era of unprecedented information access, yet a pervasive sense of intellectual poverty. The promise was clear: with the world’s knowledge a click away, we would become polymaths, effortlessly synthesizing insights across domains. The reality is a browser tab graveyard, a playlist of unfinished courses, and the nagging feeling that while we’ve consumed a lot, we’ve understood little.

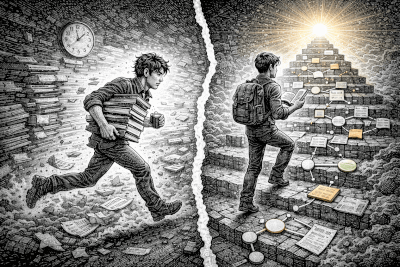

This is the modern learning paradox. In our quest for efficiency, we’ve crowned speed as the ultimate metric. We speed-watch lectures, skim articles, and binge micro-courses, mistaking the rapid accumulation of facts for the slow construction of understanding. We measure progress in pages turned or videos completed, not in connections forged or models built. The tools of our age—2x playback, speed-reading apps, endless content streams—are optimized for one thing: moving us faster through the material. They are not, it turns out, optimized for learning.

The tension lies in a fundamental cognitive mismatch. The human mind does not learn by stacking facts like bricks. It learns by weaving concepts into networks, by building internal architectures called schemas. Speed-focused methods feed the linear list; they do nothing to build the associative network. The result is a fragile kind of knowing—a collection of isolated points that lack the supporting structure to hold them in place or connect them to new ideas.

True learning acceleration, the kind that lasts and empowers, comes not from moving faster through content, but from building better internal structures to receive and connect that content. In the economy of the mind, structure is the multiplier of speed.

The Modern Learning Paradox: Speed as a False God

We have mistaken consumption for comprehension. The metrics of our digital learning environments—completion rates, watch time, streaks—are proxies for engagement, not understanding. They measure the velocity of our eyeballs, not the depth of our cognition. This conflation is seductive because it feels productive. Finishing a two-hour lecture in one hour feels like a win. Skimming three research papers in the time it used to take to read one feels like progress.

But empirical studies hint at the illusion. Research on lecture video speed found that while students felt they would perform similarly after watching at 1x or 2x speed, the relationship between speed and long-term retention is complex and often negative for complex material. The features that transform passive video watching into active learning aren't about pace, but about interaction and structure—pausing to reflect, connecting concepts, testing understanding.

Contrast this with ancient learning techniques like the memory palace, a method designed explicitly for durable recall through spatial and narrative structure. It was slow, deliberate, and architectural. Today’s “binge-learning” culture is its antithesis: fast, passive, and transactional. We have traded the labor of building a memory architecture for the ease of renting temporary mental space.

The false god of speed whispers that more, faster, is better. But the brain’s learning machinery operates on a different principle: meaning, connection, and structure are better. When we prioritize velocity, we bypass the very cognitive processes—integration, elaboration, schema formation—that make knowledge stick and become useful.

The goal of learning is not to fill a bucket, but to build a framework.

How the Brain Actually Learns: The Architecture of Knowledge

To see why structure triumphs over speed, we must look under the hood of cognition. Learning is not a transfer of data; it is the biological process of forming and strengthening synaptic connections between neurons. An isolated fact is a weak, solitary neural pathway. A connected concept is part of a robust, interconnected network—a pathway that is traveled often and linked to many destinations.

This is the core of Schema Theory. Your brain doesn’t store a random list of facts about “project management.” It has a “project management” schema—a pre-existing mental framework with slots for concepts like scope, timeline, resources, and risks. When you encounter new information about agile methodologies, your brain works to assimilate it into this existing schema. If the information fits, it is anchored firmly. If you lack a schema, the new information is “cognitively homeless,” adrift in working memory until it is inevitably forgotten.

Think of it as the difference between a pile of bricks and a cathedral. The pile (unstructured facts) is heavy and useless. The cathedral (the structured schema) is an organized, functional system where every brick has a place and purpose. The value is in the architecture.

This is where Cognitive Load Theory, pioneered by researchers like John Sweller, becomes critical. Our working memory—the mental workspace where conscious processing happens—is severely limited. It can only hold a few chunks of novel information at a time. Unstructured learning, like reading a dense text without a guide, overwhelms this space with disjointed facts, leaving no room for the deeper work of connection-making. This is called extraneous cognitive load—mental effort that does not contribute to learning.

A clear, external structure, like a concept map or a well-organized outline, performs a vital function: it offloads the organizational burden from your working memory. It externalizes the schema. You no longer have to mentally juggle how Concept A relates to B and C; you can see it on the canvas. This frees up your precious cognitive resources for germane load—the mental effort that directly contributes to building and automating those schemas in long-term memory.

This philosophy echoes the toolmaking visions of Vannevar Bush and Bret Victor. The best cognitive tools are those that externalize the structures of thought, making them visible, tangible, and manipulable. They allow us to see our own understanding, to work with it directly, and to spot its gaps and contradictions.

The High Cost of Unstructured Learning: Illusions and Fragility

Pursuing speed at the expense of structure incurs a steep, often hidden, tax on your intellectual capital. The first symptom is the illusion of competence. Watching a smooth, well-explained video at 2x speed can create a feeling of fluency. The concepts follow logically, the presenter is clear, and you nod along. This feeling is mistaken for understanding. When you later try to explain the concept or apply it, the structure collapses because you never built it yourself; you merely observed its shadow.

This leads to fragile knowledge. Facts memorized in isolation—without a structural context—are easily dislodged. You might recognize them on a multiple-choice test (a context cue), but you cannot recall them voluntarily to solve a novel problem. They are inert. You “know” it, but you can’t “use” it.

The most significant cost is the transfer problem. Knowledge learned in a vacuum fails to migrate to new situations. You might understand a statistical principle in the context of a textbook example, but fail to see how it applies to analyzing user growth for your product. Transfer depends on deep, abstract schemas that strip away surface details to reveal underlying principles. Unstructured, context-bound learning never forms these portable schemas.

Furthermore, an unstructured knowledge base stifles creativity. Innovation rarely springs from a brand-new idea; it emerges from novel connections between existing ideas. A scattered collection of facts offers few connection points. A richly structured network, however, is a playground for analogical thinking. Seeing the hierarchy of a biological ecosystem might inspire a new way to structure a software team’s responsibilities. These cross-domain insights are only possible with organized, accessible mental models.

In the long run, unstructured learning is the slower path. It necessitates constant re-learning, as unanchored facts fade. It creates mental clutter that impedes the absorption of new insights. It forces you to start from scratch with each new topic, unable to build upon a stable foundation. The initial time “saved” by speeding through content is paid back with interest through repeated effort and missed opportunities for synthesis.

Structure as a Cognitive Tool: From Passive Consumption to Active Construction

If speed is the siren song of passive consumption, then structure is the deliberate practice of active construction. Here, “structure” does not mean a rigid, imposed outline. It means any external, manipulable representation of relationships—a hierarchy, a network, a concept map, a causal diagram. It is the tangible artifact of your attempt to make sense of something.

This shifts the learner’s role from spectator to architect. Passive highlighting or copying notes is collecting fragments. Active structuring—deciding what the core idea is, what supports it, and how those supports relate to each other—is building a model. The latter is a generative act that forces comprehension. You cannot build a coherent structure around something you don’t understand.

Consider two powerful learning frameworks that implicitly prioritize structuring:

- The Feynman Technique: The act of explaining a concept in simple terms forces you to identify its core structure, strip away jargon, and clarify relationships between ideas. You are constructing a narrative schema.

- Bloom’s Taxonomy: The higher-order skills—analyzing, evaluating, creating—are all structural operations. They require deconstructing, comparing, critiquing, and synthesizing, not just remembering.

From a toolmaker’s perspective, the value of a tool like a mind map is not primarily in the final, pretty picture. The value is in the cognitive work it facilitates: the act of creating the connections, of dragging a node and asking, “Does this belong here? What is the nature of this link?” This process creates a virtuous cycle:

- Build a structure to clarify your current understanding.

- The structure reveals gaps (a lone, unconnected node; a confusing hierarchy).

- These gaps prompt targeted learning (rereading a section, researching a term).

- The new knowledge refines the structure, making it more accurate and robust.

- The improved structure enables deeper questions, and the cycle continues.

This is a self-correcting, deepening loop of learning. It is the opposite of the linear, consume-and-complete model.

A Practical Framework: Building Durable Knowledge, Not Just Checking Boxes

How do we operationalize this shift from speed to structure? It requires changing both mindset and method.

| Principle | The Speed Mindset | The Structure Mindset |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Point | Dive in headfirst, start reading/watching. | Map Before You Dive. Survey the material. Use a summary, abstract, or table of contents to sketch a skeleton map of core concepts and their suspected relationships. |

| Success Metric | Finishing the chapter, video, or article. | Learn to Fill the Map, Not Finish the Material. Your goal is the completion and refinement of your knowledge structure. The source material is just the clay. |

| Approach to Difficulty | Avoid friction; skip confusing parts to maintain pace. | Embrace the Friction of Construction. The struggle to connect a new, confusing idea to your existing map is . Sit with it. |

| Tool Selection | Linear note-taking apps, passive video players. | Use Tools That Externalize Structure. Use tools that allow visual manipulation of relationships. The physical act of dragging a node to reorganize a hierarchy is a cognitive act. |

| End State | Archive notes, never to be seen again. | Iterate, Don’t Archive. Your knowledge structure is a living document. Revisit and reorganize it as your understanding deepens. The final form is less important than the process of its evolution. |

For example, when approaching a new research paper, don’t just read it linearly. First, glance at the abstract and headings to create a bare-bones mind map with the main claim, methods, and key findings as nodes. As you read, add details as child nodes. When you hit a complex term, pause to add a defining node. If the discussion section challenges your initial understanding, restructure the map. The tool should facilitate this fluid, constructive process. In my own work building ClipMind, this is the core interaction we optimize for: not just presenting a summary, but providing an editable structure that invites this kind of active, deepening engagement.

Beyond Efficiency: Structure as a Path to Wisdom and Agency

Ultimately, this is about more than efficient recall for an exam. It is about cultivating agency—the capacity to wield knowledge effectively in uncertain, novel situations. Structure grants this agency. A well-organized mental model allows you to navigate complexity, to generate hypotheses, and to make informed decisions when there is no clear textbook answer.

This connects directly to critical thinking. When you encounter a new claim, you don’t evaluate it in isolation. You check it for consistency within your existing, structured network of knowledge. Does it fit with established evidence? Does it create a contradiction that needs resolving? Does it fill a gap you had already identified? This is a far more robust defense against misinformation than a collection of disjointed “facts.”

We might even think of wisdom as connected knowing. It is the ability to see patterns across disparate domains—to recognize that the growth loops in a startup mirror feedback mechanisms in ecology. This pattern recognition is the hallmark of a richly interconnected, well-structured mind.

As a toolmaker, this is the ethos that guides the work. We don’t build tools to merely save time. We build them to create time for deeper thinking. We use AI not to think for us, but to handle the initial, labor-intensive work of extracting and proposing a structure from raw information—like summarizing a lengthy video into a navigable map. This automation offloads the extraneous load, so the human mind can be freed for the higher-order, irreducibly human work of synthesis, critique, and creation.

In an age of infinite information, the scarce resource is no longer access, but meaning. Structure is the machinery of meaning-making. It is the slow, deliberate craft of turning information into understanding, and understanding into agency. In a world optimized for shallow consumption, prioritizing structure is the only way to learn deeply.