We summarize to understand, yet most summaries leave us more confused than before. You’ve likely felt it—the frustration of reading a perfectly condensed paragraph about a complex topic and still not grasping how the pieces fit together. The information is there, but the meaning is missing.

This is the paradox of modern summarization. We have more tools than ever to shrink text, but we’ve conflated brevity with clarity. The result is a landscape of linear bullet points and dense AI paragraphs that treat a research paper like a grocery list, presenting items without showing the recipe. The true architecture of the document—the load-bearing arguments, the supporting evidence, the hidden connections—remains invisible. We are given a pile of bricks and told it’s a blueprint.

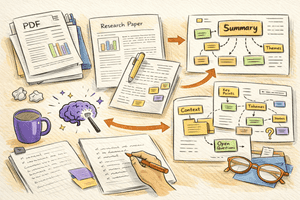

The problem isn’t the amount of information; it’s the form. When we reduce a system of ideas to a sequence of sentences, we destroy the very relationships that give it meaning. This article explores a different path: moving beyond shrinking text to revealing structure. It’s about building scaffolds for thought, not just shorter documents.

The Flaw in the Linear Lens

Most summarization tools operate on a fundamental misconception: that a document is a sequence of words to be shortened. They produce linear text—a paragraph or a bulleted list—that mirrors the original’s order but strips away its conceptual hierarchy. Every point appears with equal visual weight, forcing your brain to do the heavy lifting of reconstructing importance and connection from a flat list.

This creates cognitive friction. A study on text structure highlights how hierarchical presentation aids recall compared to linear text. When you read a traditional summary, your working memory is overloaded holding multiple discrete facts, trying to piece together a model the summary itself failed to provide. The purpose of summarization—to reduce cognitive load—is defeated by its own format.

Consider a research paper. Its value isn’t in the sequence of “Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion.” It’s in the relationship between the hypothesis and the experimental design, the way data informs the conclusion, and how limitations frame future work. A linear summary turns this dynamic system into a static list. You get the “what” but lose the “why” and “how.” The fundamental tension is clear: we summarize to reduce information, but reduction without intelligent structure creates information loss, not clarity.

The most accurate summary can still be a poor tool for understanding if it fails to show how ideas relate.

Seeing the System, Not the Sequence

A complex document is not a narrative to be condensed; it is a system to be mapped. Its ideas exist in a network of dependencies, support, and contradiction. The traditional act of reading is inherently sequential, forcing our brains to perform the inefficient task of reconstructing this network from a stream of words—like trying to understand a city’s layout by walking its streets in a random order.

Cognitive science offers a better way. Research into spatial cognition and cognitive maps shows that our brains are exquisitely tuned to understand complex information through spatial and visual representation. We navigate conceptual spaces using the same mental machinery we use to navigate physical ones. A study on creating visual explanations found that visually representing a system’s elements and their spatial or metaphoric relationships leads to deeper learning.

The shift required is from summarizing content to mapping structure. Instead of asking “What does it say?”, we must ask “How is it built?”. What is the central thesis? What pillars of evidence support it? What are the counterpoints or limitations? This systemic view reveals the document’s true intellectual architecture, transforming it from a text to be read into a territory to be explored.

The Anchoring Power of Hierarchy

Effective document comprehension begins with hierarchy. Hierarchy is the inherent scaffolding of thought; it distinguishes a core argument from an illustrative example, a primary cause from a secondary effect. A summary that preserves and visualizes this hierarchy does not merely shorten—it clarifies.

A hierarchy-first approach acts as an automatic filter for noise. In a 50-page market report, this method immediately surfaces the three or four key market drivers at the center. Repetitive data tables, boilerplate methodology sections, and tangential competitor profiles recede to appropriate supporting branches. The visual weight of the map corresponds to the conceptual weight of the ideas. You see what matters most, first.

This is where tools designed for visual structuring, like ClipMind, operationalize this principle. By analyzing a document and extracting its key concepts into an editable visual map, the tool provides the hierarchy-first scaffold. The core argument becomes the central node; supporting evidence and examples branch out logically. The result is not a random assortment of important sentences, but an intelligently organized representation of the document’s skeleton. You are shown the framework, allowing you to focus on evaluating its strength and connections.

The Interactive Leap: From Consumer to Co-Creator

The deepest cognitive shift occurs when summarization stops being a passive output and becomes an interactive process. Reading a static summary is consumption. Manipulating a visual summary is construction. This shift from consumer to co-creator is where comprehension solidifies into knowledge.

When a summary is an editable visual structure, you engage with it differently. You can drag a “limitation” node closer to a “finding” to question their relationship. You can merge a “methodology” branch from one research paper with another’s to compare approaches. You can add a personal note or question directly onto a concept. This active manipulation transforms the document from an external artifact into a part of your own thinking process.

The evidence for this is compelling. A meta-analysis of 37 studies on concept mapping in STEM education found a moderate overall positive effect on student achievement. The act of creating or manipulating visual knowledge structures—engaging in what researchers call “knowledge integration”—leads to better outcomes than simply reading prepared summaries. Another study noted that creating visual explanations improves learning more than generating text summaries. The tool provides the scaffold, but the thinker, through interaction, builds the insight.

Closing the Loop: The Integrated Knowledge Workflow

True understanding is rarely the end goal; it is the foundation for synthesis, critique, and creation. Therefore, the ideal summarization tool shouldn’t be a dead-end, but a bridge in a larger workflow: Read, Map, Think, Write.

- Ingest & Structure: The tool analyzes the PDF, paper, or report, extracting key concepts and presenting them in an editable visual map. This is the “Map” phase.

- Synthesize & Connect: You, the thinker, interact with the map. You merge insights from other documents, ask questions of the AI assistant, identify gaps in logic, and rearrange nodes to reflect your evolving understanding. This is the active “Think” phase.

- Output & Create: The visual structure seamlessly converts into a linear outline. With a click, your mind map becomes a Markdown document, a set of bullet points for a presentation, or a structured draft for a paper. The “Write” phase is now guided by the clear architecture you built during thinking.

This workflow acknowledges that summarization is not about creating a smaller document to file away. It’s about creating a better thinking tool to build upon. It closes the loop between consumption and creation, ensuring that the effort of understanding directly fuels the ability to communicate and innovate.

The Partnership: Why AI Needs Architecture

Modern AI is astonishingly good at identifying what matters in a text. It can condense 10,000 words into 200 with impressive accuracy. But if those 200 words are presented as a dense, linear paragraph, the cognitive burden on the human reader remains frustratingly high. The machine has done the work of selection, but not the work of presentation.

The breakthrough happens in the partnership between AI-generated insight and human-centric information architecture. AI identifies the “what.” Visual structure reveals the “how” and “why.” This respects the natural division of cognitive labor: machines excel at processing information at scale and identifying patterns in language; humans excel at perceiving spatial relationships, sensing gaps, and drawing novel connections from structured displays.

This is the hybrid intelligence that defines the next step in document understanding. It’s not about more sophisticated text generators; it’s about smarter cognitive interfaces. The future lies in tools where AI handles the analytical heavy lifting of parsing text, and the interface is designed to present the results in a way that aligns with—and augments—the way the human mind best understands complex systems.

Summarization as Scaffolding

The best way to summarize a PDF, research paper, or long document is not to make it smaller, but to make its architecture visible. It is to move from providing a pile of extracted parts to providing a blueprint that shows how they fit together.

When you can see the relationships between ideas at a glance, you understand the document’s true meaning faster and more deeply. You transition from decoding information to engaging with meaning. This approach transforms summarization from a clerical chore into the foundational, active first step of genuine knowledge construction.

Seek tools that help you build mental models, not just shorten text. Your comprehension will expand, even as the document contracts. The goal is not a smaller pile of bricks, but the clear, buildable scaffold for your own ideas.