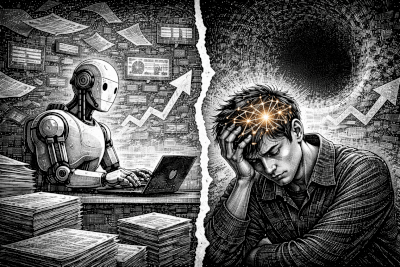

We measure productivity in words per minute, tasks completed per hour, and summaries generated per second. Our tools are calibrated for throughput, and we celebrate the metrics. Yet, a quiet unease grows among the most prolific. The more we produce, the less we seem to grasp. The faster we generate answers, the more elusive understanding becomes.

This is the central paradox of our AI-augmented age: we have built engines of immense output that may be engines of diminishing insight. The very tools designed to make us smarter risk making our thinking more superficial. To understand why, we must look beyond the dashboard of productivity and into the cognitive mechanics of how we learn, think, and remember.

The Efficiency Paradox: More Output, Less Insight

The data is clear: AI tools boost measurable productivity. A Microsoft research initiative found that early LLM-based tools provide "meaningful boosts" to the speed and accuracy of tasks for information workers. We can draft, summarize, and iterate at a pace that was unimaginable a decade ago. But this quantitative gain masks a qualitative loss. The same surge that fills documents with text can leave minds empty of durable knowledge.

Surveys of knowledge workers reveal a telling tension: they feel more productive but report self-reported reductions in cognitive effort and confidence. The tool completes the task, but the user feels a step removed from the understanding that should have been forged in the process. This is not a failure of the individual, but a flaw in the design paradigm. We have optimized our systems for the throughput of information, not for the formation of insight.

Vannevar Bush, in his seminal 1945 essay "As We May Think," foresaw a world drowning in information. His proposed solution, the "memex," was a tool for association and trail-blazing—a system to extend understanding. Today, we have automated the flood he warned against, but we have largely neglected to build the cognitive life rafts. The challenge is no longer access to information; it is the digestion and synthesis of it. The real productivity metric we should care about is not output per hour, but understanding per idea.

The goal of a tool should be to deepen comprehension, not just to accelerate production.

The Mechanics of Cognitive Offloading: What We Gain and What We Lose

"Cognitive offloading" is the act of delegating mental work—like summarizing, structuring, or connecting ideas—to an external system. AI is the most powerful offloading device we've ever invented. The immediate benefits are obvious: our working memory is freed, we can handle larger volumes of data, and we can iterate rapidly.

The costs, however, are subtle and cumulative. When we outsource synthesis, we atrophy our synthesis muscles. The crucial neural connections that form when we manually wrestle with concepts, draw links, and build our own structures are short-circuited. Cognitive science identifies this as the generation effect: we remember and understand information far better when we generate it ourselves than when we passively receive it, even if the received version is "better."

Think of it like physical fitness. If a machine lifts all the weights for you, your muscles weaken. Similarly, if AI handles the heavy lifting of analysis and structuring, your capacity for those very tasks diminishes over time. Studies are beginning to document this "skill fade." Research into cognitive automation warns of a vicious circle of skill erosion, where reliance fosters complacency and weakens mindfulness. Another analysis suggests AI assistance might accelerate skill decay among experts and hinder skill acquisition for novices.

We gain speed and scale, but we risk losing the deep, embodied knowledge that comes from the struggle. The path of least resistance in using AI is often the path of least understanding.

Interface Design That Prioritizes Output Over Understanding

The problem is cemented by our dominant AI interface design: a blank box. You type a prompt, and you receive a block of text. This design casts the AI as an oracle, not a thinking partner. It delivers answers but obscures reasoning. It provides conclusions but hides the scaffolding.

This linear, opaque output is optimized for consumption, not comprehension. It gives you the "what" but rarely reveals the "how" or the "why." Contrast this with tools built for thinking—concept maps, argument maps, or detailed outlines. These tools externalize structure, making the relationships between ideas visible, inspectable, and manipulable. They turn thinking into a tangible artifact you can refine.

Bret Victor's vision of "Explorable Explanations" is instructive here. He argues for systems where users can "see" and "manipulate" the underlying model to build understanding. Most AI interfaces do the opposite: they present a finished model, sealing it in a textual container. The next frontier is not AI that generates more impressive final drafts, but AI that helps you build and explore the draft's underlying structure.

From Passive Consumption to Active Co-creation: A New Model

The way forward requires a shift in model: from AI as a substitute for thinking to AI as a catalyst for thinking. The goal is cognitive coupling, where the tool engages you in the process of constructing understanding. In this model, AI suggests structures, highlights gaps, and proposes connections, but the user remains the active editor, synthesizer, and meaning-maker.

Visual-spatial representations are key to this. A mind map or concept map grounds abstract ideas in a form you can see, rearrange, and interrogate. It transforms a monologue from the AI into a dialogue with your own thoughts. The principles for tools that increase understanding become clear:

- Interactive: You can touch and change the output.

- Structural: The output reveals relationships, not just sequences.

- Provisional: It is easy to edit, encouraging iteration.

- Traceable: You can see the path of your own reasoning.

This is a return to the original augmentation vision of pioneers like Douglas Engelbart, who built tools to extend human intellect, not replace it. It’s the difference between a tool that writes a report for you and a tool that helps you see the connections in your research so clearly that you can write a better report yourself.

Building a Personal Practice of AI-Augmented Understanding

We cannot wait for the perfect tool. We can, however, use existing tools more mindfully to guard against cognitive erosion and promote deeper understanding.

- Use AI for "First Drafts of Understanding": Let AI generate the initial summary or outline, but treat it as raw material. Your mandatory next step is a manual revision where you rephrase, reconnect, and question every point. This engages the generation effect.

- Favor Structural Outputs: Choose tools that output to editable, visual formats. The act of manipulating a mind map or reorganizing an outline forces cognitive engagement that scrolling through a text block does not. For instance, using a tool to summarize a webpage directly into a mind map creates an artifact you must actively parse and can immediately restructure.

- Position AI in the Middle of Your Workflow: Don't start or end with AI. Start with your own messy notes or questions. Use AI to expand, challenge, or organize that starting point. Then, finish by refining the structure and writing the final synthesis yourself. This keeps you in the driver's seat.

- Practice Explanation-Driven Learning: Ask AI to explain a concept. Then, close the AI and try to teach the concept back—to yourself, a colleague, or an imaginary audience. The gaps you discover are where your true learning begins.

The goal is a symbiotic workflow. Let AI handle scale, pattern recognition, and initial drafting—the cognitive heavy lifting. Reserve for yourself the uniquely human tasks of judgment, synthesis, meaning-making, and the final creative act of expression.

Conclusion: Recalibrating the Purpose of Our Tools

We stand at an inflection point. We have proven that AI can dramatically increase output. The pressing question now is whether we can design AI that dramatically increases understanding.

The next generation of intelligent tools should be judged not by how many words they save us, but by how much clearer they help us think. They should help us ask better questions, not just provide faster answers. They should make our reasoning visible and our knowledge structures malleable.

As both builders and users of these tools, we must recalibrate our values. We must prioritize comprehension metrics alongside productivity metrics. We must seek tools that invite us into the process, that treat thinking as a collaborative act between human and machine. The real augmentation of human intelligence lies not in outsourcing our thought, but in designing systems that deepen, extend, and illuminate our innate capacity to understand.