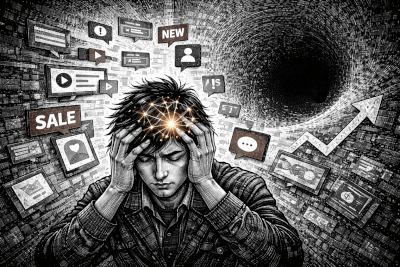

We have more access to knowledge than any previous generation, yet we feel less capable of understanding complex topics. The experience is now universal: you open fifteen browser tabs, skim three articles simultaneously, and an hour later, you can recall nothing but a vague sense of anxiety. The problem is no longer finding information; it’s making it meaningful. We live in the age of information abundance, yet we suffer from a scarcity of understanding.

This paradox defines modern learning. We have inherited tools—browsers, PDF readers, note-taking apps—designed for consumption, not comprehension. They present knowledge as a linear stream, a format that conflicts with the associative, networked nature of human thought. The result is cognitive overload, a state where our working memory is flooded, and nothing sticks. To move forward, we must examine how our tools shape our thinking, why current AI solutions fall short, and how visual structuring systems can offer a path from overload to genuine insight.

The Paradox of Modern Learning

Five centuries ago, the printing press unleashed the first great wave of information overload. Scholars like Conrad Gessner lamented the “confusing and harmful abundance of books.” Societies adapted with new cognitive tools: commonplace books for collecting quotes, and elaborate indexing systems to manage the flood. Today, we face a similar, yet exponentially larger, cognitive event. The digital universe is projected to hold over 181 zettabytes of data by 2025. Our tools for accessing this data are miraculous, but our cognitive architecture has not evolved.

The tension is clear in the data. Research into digital media consumption shows that while we ingest more information, our retention and deep understanding often suffer. A systematic review on information overload notes that the sheer volume can lead to “impaired decision-making and reduced satisfaction.” We are in a state of constant, shallow processing—skimming headlines, jumping between sources, and engaging in media multitasking that taxes working memory. The historical lesson is that periods of information explosion demand new methods of organization. The printing press gave us the index and the footnote. The internet gave us the hyperlink and the search engine. The AI era demands a tool for synthesis.

The core issue is not the information itself, but the lack of a structure to make it cohere. We have optimized for discovery at the expense of digestion. The modern learner’s struggle is the struggle to build a personal, durable knowledge structure from an endless, unstructured feed.

How Our Tools Shape Our Thinking

Our default interfaces enforce a way of thinking that is at odds with our neurology. The browser tab, the infinite scroll, the PDF pagination—all present information as a sequential, linear path. You must process point A before you reach point B. This conflicts with how human memory and understanding actually form: through association, hierarchy, and spatial relationship.

Cognitive science tells us that our working memory is severely limited, capable of holding only about 5 to 9 chunks of information at any given time. When we read linearly while mentally trying to connect ideas back to earlier points or across different tabs, we incur a massive extraneous cognitive load. This is the mental effort spent on managing the tool and the disparate pieces, rather than on building understanding. The constant context switching between sources, with no relational map, ensures that ideas remain isolated fragments.

The most profound technologies are those that disappear. They weave themselves into the fabric of everyday life until they are indistinguishable from it. — Mark Weiser

Our current tools have not disappeared; they constantly demand our attention for navigation and management. Contrast this with pre-digital tools that had physical constraints which aided cognition. A scholar’s commonplace book, as described by John Locke, forced organization by topic. The physicality of index cards created a spatial arrangement of ideas that could be shuffled and related. These tools provided cognitive ergonomics—they reduced the extraneous load of organization, freeing the mind for deeper thought.

Today’s digital note-taking apps often mimic the blank page, offering freedom but no initial structure. Starting from a blank slate with complex source material is cognitively expensive. The tool should provide the scaffolding, not just the lumber. We need interfaces that start with structure, that externalize the relational thinking our minds are trying to do internally, so we can see our thoughts and refine them.

The False Promise of AI Summarization

The intuitive response to information overload has been to deploy AI as a summarizer. Tools that condense a long article or video into a few bullet points promise efficiency. But this creates a second-order problem: it confuses information retrieval with knowledge construction. Reading an AI summary is a passive act. You receive the conclusions without traversing the logical path that led to them. You get the answer, but you don’t build the mental model.

Studies on AI in education hint at this cognitive paradox. While AI can personalize learning, excessive reliance may reduce cognitive engagement and long-term retention. If the thinking is done by the AI, the student may lose the intrinsic motivation and cognitive effort required to solidify understanding. This aligns with the theory of desirable difficulties—learning conditions that feel harder in the moment, like self-testing or spaced repetition, lead to stronger long-term retention. Passive consumption of AI summaries removes all desirable difficulty.

Furthermore, current large language models have inherent limitations in preserving the hierarchical and relational information crucial for deep understanding. Research has shown they can struggle with establishing reliable instruction hierarchies and reasoning over complex knowledge graphs. A summary is a flat list; knowledge is a multi-dimensional network.

The vision of Vannevar Bush’s Memex was not of a machine that thinks for you, but of a device that augments your memory and associative trails. The goal should be active structuring, not passive summarization. The ideal AI tool would not give you the blueprint; it would help you draw your own, based on the materials you’ve gathered.

Visual Structure as Cognitive Scaffolding

The human brain is inherently visual-spatial. We navigate the world and remember it through relationships in space. This is why visual organization tools can be so powerful—they map directly onto our cognitive strengths. Research consistently shows the superiority of graphics over text in long-term memory retention for conceptual information, as they facilitate the creation of coherent mental models.

Mind maps, concept maps, and other node-link diagrams work because they externalize working memory. They make the connections between ideas explicit, reveal hierarchy at a glance, and turn abstract relationships into concrete spatial ones. Studies on concept mapping show it can reduce cognitive load and increase academic achievement. By offloading the organization from your mind to the canvas, you free up cognitive resources for analysis, critique, and creation.

However, traditional mind mapping has a fatal flaw for the modern knowledge worker: it requires manual input. To build a map from a 50-page PDF or a 60-minute lecture, you must first understand the content well enough to extract and structure its key points—the very task you’re using the map to accomplish. It’s a catch-22.

The bridge is AI that extracts structure, not just text. Imagine a tool that reads the PDF for you and proposes a first-draft mind map—a skeletal structure of main arguments, supporting evidence, and their relationships. This is not the final product, but the starting point. Like an architectural blueprint, it provides the essential framework which you then inhabit, modify, and make your own. This shifts the user’s role from scribe to editor, from builder to architect. The cognitive effort moves from initial structuring (high load) to critical evaluation and refinement (deep processing).

Building Tools for Augmented Cognition

The principles for the next generation of thinking tools become clear. They must be proactive, not passive. They should start with a proposed structure derived from your source material—a webpage, a video, a research paper. This structure must be fully editable, because the act of manipulation is the act of learning. Dragging a node, merging two branches, or adding a personal insight are cognitive actions that internalize knowledge.

These tools should also offer dual-view cognition, acknowledging that we think in networks but often communicate in sequences. A visual map is ideal for understanding relationships and brainstorming. A linear outline or Markdown view is essential for drafting an article or report. The ability to seamlessly switch between these views allows the tool to support the entire workflow from research to composition. As I’ve built tools for visual thinking, this duality has been a core tenet—the map and the document are two faces of the same intellectual coin.

This philosophy echoes the work of pioneers like Bret Victor, who argued for responsive tools that show the consequences of your thinking in real time. The tool should be a co-pilot, not an autopilot. It should handle the computationally intensive task of initial pattern recognition (What are the main ideas here?) and present them in a malleable form. The human then provides the judgment, creativity, and contextual wisdom to refine that pattern into knowledge. This collaborative loop between human and machine—where AI handles structure-finding and humans handle sense-making—is the model for augmented cognition.

From Overload to Understanding

The path forward is not to seek tools that help us consume information faster. The path is to build tools that help us understand it better, with less cognitive strain. The goal is to transform information abundance from a source of anxiety into a foundation for insight. Effective learning in this new paradigm begins with a structured overview—a visual map that gives you the lay of the land. From this high ground, you can see the connections and choose where to dive deep.

The implications extend beyond personal productivity. When we can more easily structure complex information, we improve decision-making, foster creativity, and enhance collaborative problem-solving. The ability to quickly see the relationships between market forces, technological trends, and social dynamics is a profound advantage.

We stand at the confluence of two powerful streams: the vast ocean of digital information and the rising capabilities of artificial intelligence. The choice is how we channel them. We can use AI to simply shrink the ocean into more manageable droplets, or we can use it to build intellectual vessels—tools of thought—that allow us to navigate the ocean purposefully. The most valuable skill in the age of AI may not be prompting an LLM, but knowing how to structure one’s own thinking. The tools we build next will determine whether we drown in the data or learn to sail by the stars.